Douglas and Kristine Tompkins - Regional Scale Conservation Philanthropy

More than once, I've heard it mentioned in hiking circles that the Patagonia clothing company has bought up a lot of land in Patagonia and given it back to the Chilean government on condition that it remains a National Park. That's not quite true but there is a strong connection and, as it turns out, there is a story to tell that is every bit as inspiring as you could possibly hope.

Figuring out what has gone on between millionaire conservationist clothing company owners, national governments, and local communities in Patagonia is not as easy as you might think. But it gets a whole lot easier after you stumble across one name in particular. In the 1960s, skiing and climbing enthusiast, Douglas Rainsford Tomkins, started an outdoor gear company called The North Face. The company was very successful but some years later, Tompkins decided to sell his shares in it so that he could help set up a new fashion firm, 'Esprit', with his then-wife, Susie Tompkins Buell. Meanwhile a friend of his, renowned climber Yvon Chouinard, had set up the Patagonia clothing brand, hiring Kristine McDivitt Wear (a competitive skier) to work in the fledgling business, eventually appointing her as its CEO. In amongst all this, Tompkins and Chouinard found time to undertake some impressive climbing expeditions in Patagonia, with Tompkins also pursuing interests in adventure film making and white water kayaking. In his work life, Tompkins' flair for brand development helped turn Esprit into an iconic business of the 1980s. The company was a phenomenal success, although his marriage to Susie didn't do quite so well and they separated towards the back end of the 80s. Around this time, Tompkins also seems to have become increasingly uncomfortable with the lack of environmental ethics in the fashion industry. He sold his share of Esprit back to Susie and disposed of all his associated interests and assets between 1989 and '94 so that he could concentrate his considerable energy (and accumulated wealth) on environmental projects.

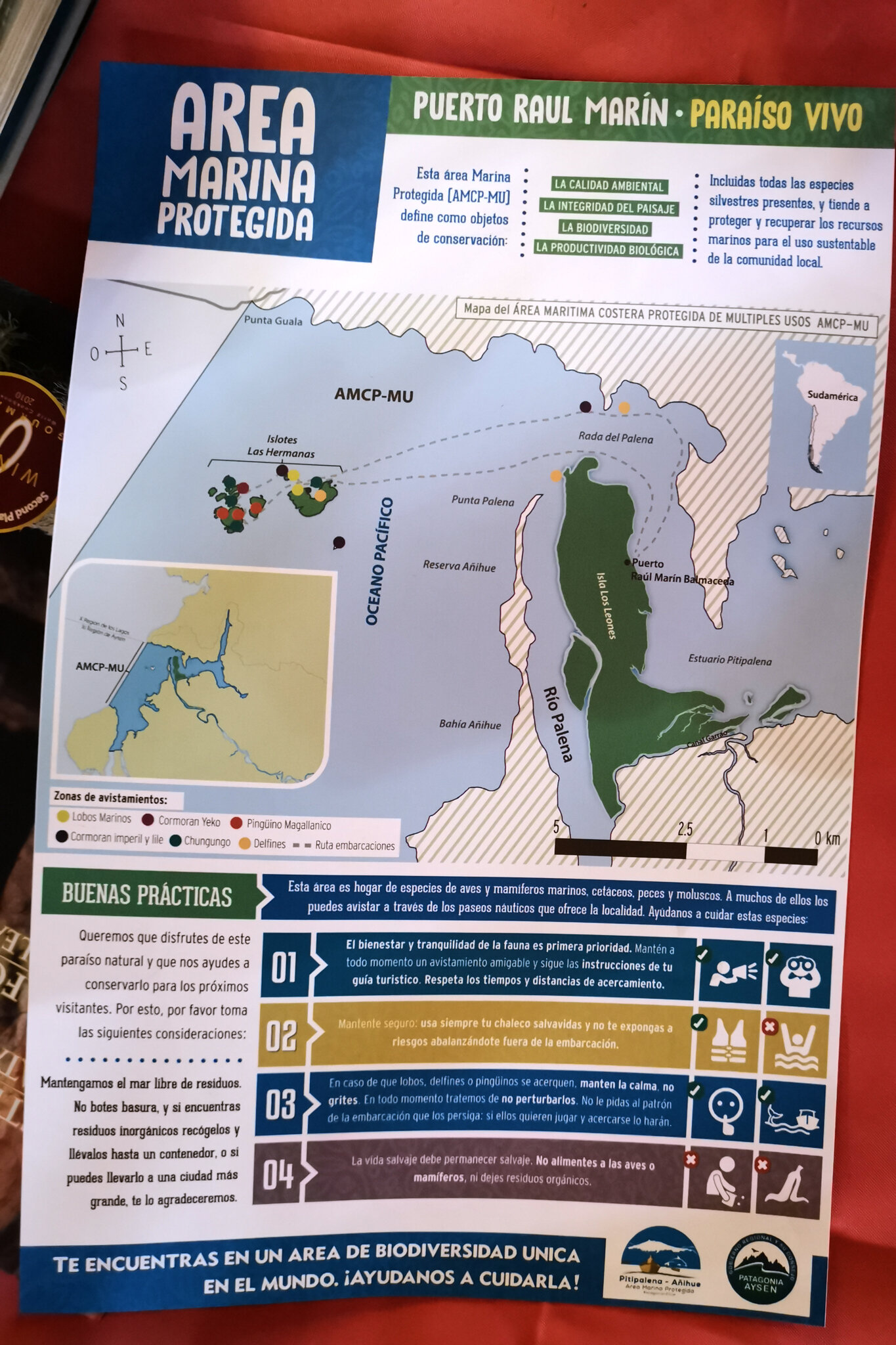

In 1991 Tompkins bought a semi-abandoned farm in the Palena region of Chile. Palena is mostly temperate rain forest, some of it ancient, with some trees that are thought to be 3,000 years old. The aim was to turn the acquired land over to organic production and conservation, protecting it from unsustainable logging and other forms of exploitation that would be harmful to its ecosystems. A year later Tompkins founded an organisation called the Conservation Land Trust (CLT) and, over the next decade, used this entity to buy up over 700,000 acres of contiguous land for the same purpose, mostly from absentee landlords. In 2007 the entirety of the land owned by CLT in the region was donated to Fundación Pumalín, a Chilean foundation formed specifically to manage what is now Pumelin Park. A key condition of the donation was that the Chilean government would guarantee the protection and conservation of the land in perpetuity.

Also during this period, Tompkins met and married the above-mentioned Kristine McDivitt Tompkins, nee Wear (in 1993). It was early in their marriage (perhaps on their honeymoon?) that the couple first drove through the Chacabuco Valley in Chilean Patagonia, then given over mainly to livestock grazing, and imagined what it could be like if it were rewilded. (Bearing in mind, the term 'rewilding' didn't even exist at that time. Doug and Kristine were true pioneers). So the CLT/Tompkins Model (my phrase) was adapted and applied to the area that has now become Parque Nacional Patagonia. That is, the extensive Estancia Valle Chacabuco was purchased in 2004, it's livestock was responsibly sold off, and a process of restoring grasslands and forests was begun which would slowly and naturally restore wildlife populations. Crucially, the Chacabuco Valley Estancia runs between two existing protected areas, Jeinimeni in the North and Tamango in the South, so that these three sub-reserves now form one contiguous protected area. In 2015, management of the park was handed over to CONAF, the Chilean national parks authority.

However, Pumelin and Patagonia national parks are only part of the story. The Tompkins Conservation* lists the following major land purchases and donations from 1991 onwards. (Pumelin and Patagonia NP are in bold).

1991-2015 711,000 acres - Pumelin Park (Eventually 727,000 acres donated to Pumalin Foundation, 2007)

1994 - 208,000 acres - Corcovado National Park (with Peter Buckley, former CEO of Esprit. Federal land later added and Corcovado NP created in 2005, totaling 726,000 acres)

1997-2007 - 350,000 acres - Iberá wetlands, Argentina

1998 - 94,000 acres - Estancia Yendegaia, Tierra Del Fuego (plus 276,000 acres of adjacent government land added in 2013)

2000 - 165,000 acres - Monte Leon NP Argentina

2002 - 272,000 acres - Iberá Wetlands (Pérez-Companc forestry company, various tree plantations and cattle ranches)

2004 - 175,000 acres - Estancia Valle Chacabuco, Aysen Province, Chile

2008 - 21,000 acres - additional purchase for Patagonia NP (huemul deer-puma interaction study)

2013 - 37,000 acres - El Rincon property donated to Perito Merino NP in Argentina

*(Tompkins Conservation became the umbrella name for CLT and other organisations founded by Tompkins for the purpose of conservation - website, including details of most of the projects noted above can be found here: http://www.tompkinsconservation.org/home.htm)

Even just taking headline figures, Tomkins purchased and GAVE AWAY somewhere north of 2 million acres of land in South America. That's about half the land area of all of the national parks in England and Wales. Another comparison, the land area of Cyprus is about 2,286,000 acres. On top of that, numerous farms and ranches have been purchased and turned over to organic and habitat-preserving production. It is an incredible story of determination, vision and generosity.

Reading around various articles and websites, it becomes apparent that relations between Tompkins Conservation and the Chilean authorities have not always been easy. Because of the large scale of the estates involved in these projects, they have been seen by some as an impingement on Chilean sovereignty, even a threat to national security, and at one stage it was seriously (though inexplicably) mooted that Tompkins might be attempting turn parts of Chile into a 'Zionist Enclave'. In fairness, you can understand some disquiet when a foreigner buys up large areas of land in a given country and then begins to influence or even control economic activity in those areas. Some of these conflicts have been practical rather than just imagined. For some time there have been plans for hydroelectric power plants in Patagonia that would provide cheap energy for Chile, but would flood large areas of land. Tompkins was active in the 'Sin Represas' campaigns against these projects, actively encouraging local opposition. But it probably says a lot about their personal qualities that Doug and Kristine were mostly able to win the trust and cooperation of both government officials and local people in their work. They were resident in Chacabuco for many years and I believe Kristine still is. It probably wouldn't have been possible to undertake projects of this kind 'from afar'. There are bags of examples of Tompkins Conservation engaging closely with local communities throughout its whole history, including assistance with establishing schools in remote areas, community waste management initiatives, and funding of individual and small NGO projects. Local economic impacts also have also been actively considered - for example, the livestock that came with the Chacabuco Estancia purchase was sold off gradually to avoid skewing prices in the local market.

There is an often repeated pattern when you start to read about ambitious conservation projects in general. They absolutely require the consent and participation of local people, but in return they can create long-term employment and economic stability as well as helping to preserve traditional professions and ways of living with nature. The alternatives - indiscriminate logging, mineral extraction and intensive agriculture - can be relatively fleeting, are subject to the whims of international markets, and eventually send ecosystems and rural communities into irretrievable decline. I suspect that pulling all these interests and apparently conflicting needs into cooperation can only be achieved with rare individual devotion and vision. The story of Tompkins Conservation clearly shows that conservation at regional level is not a simple question of money. The knowledge required, the problem solving, administration, diplomacy, sensitivity to local, regional, and national concerns, minute attention to the myriad factors affecting land use and management, not to mention the sheer physical labour involved... are staggering.

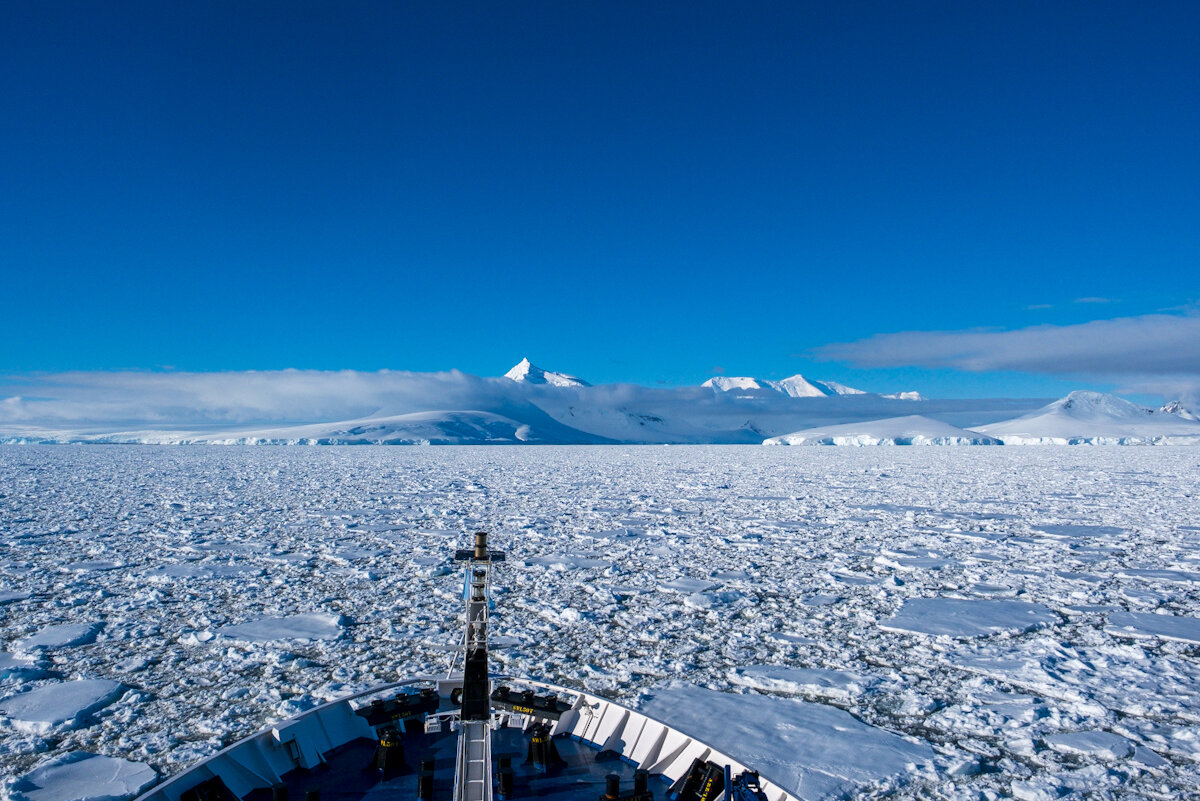

So... in spite of the name and the stories that sometimes circulate, the Patagonia clothing co. has not itself purchased land in Patagonia, although the company (and Yvon Chouinard personally) have been instrumental in many other environmental initiatives and Kristine cites Yvon as a mentor and major influence on her life. The three of them were obviously very close and clearly shared the same passions and values. I say 'were' because Doug tragically died in 2015 after a kayaking accident on Lago General Carrera, on the northern border of Parque Nacional Patagonia. (Yvon was actually with the group that went out on the water that day). Kristine continues to lead and develop Tompkins Conservation with ongoing projects in Chile and Argentina. Doug is buried at a small cemetery in Chacabuco Valley.

Visiting Parque Nacional Patagonia